Super resolution microscopy

Super-resolution microscopy is a form of light microscopy. Due to the diffraction of light, the resolution of conventional light microscopy is limited as stated by Ernst Abbe in 1873.[1] A good approximation of the resolution attainable is the FWHM (full width at half-maximum) of the point spread function, and a precise widefield microscope with high numerical aperture and visible light usually reaches a resolution of ~250 nm.

Super-resolution techniques allow the capture of images with a higher resolution than the diffraction limit. They fall into two broad categories, "true" super-resolution techniques, which capture information contained in evanescent waves, and "functional" super-resolution techniques, which uses clever experimental techniques and known limitations on the matter being imaged to reconstruct a super-resolution image.[2]

True subwavelength imaging techniques include those that utilize the Pendry Superlens and Near field scanning optical microscopy, the 4Pi Microscope and structured illumination microscopy technologies like SIM and SMI. However, the majority of techniques of importance in biological imaging fall into the functional category.

There are two major groups of methods for functional super-resolution microscopy:

- Deterministic super-resolution: The most commonly used emitters in biological microscopy, fluorophores, show a nonlinear response to excitation, and this nonlinear response can be exploited to enhance resolution. These methods include STED, GSD, RESOLFT and SSIM.

- Stochastical super-resolution: The chemical complexity of many molecular light sources gives them a complex temporal behaviour, which can be used to make several close-by fluorophores emit light at separate times and thereby become resolvable in time. These methods include SOFI and all single-molecule localization methods (SMLM) such as SPDM, SPDMphymod,PALM, FPALM, STORM and dSTORM.

Contents |

History

In 1978, the first theoretical ideas had been developed to break this barrier using a 4Pi Microscope as a confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscope where the light is focused ideally from all sides to a common focus that is used to scan the object by 'point-by-point' excitation combined with 'point-by-point' detection.[3] Some of the following information was gathered (with permission) from a chemistry blog's review of sub-diffraction microscopy techniques Part I and Part II. For a review, see also reference.[4]

True super-resolution techniques

Near-field scanning optical microscope (NSOM)

Near-field scanning is also called NSOM. Probably the most conceptual way to break the diffraction barrier is to use a light source and/or a detector that is itself nanometer in scale. Diffraction as we know it is truly a far-field effect: The light from an aperture is the Fourier transform of the aperture in the far-field.[5] But, in the near-field, all of this is not necessarily the case. Near-field scanning optical microscopy (NSOM) forces light through the tiny tip of a pulled fiber — and the aperture can be on the order of tens of nanometers.[6] When the tip is brought to nanometers away from a molecule, the resolution is limited not by diffraction but by the size of the tip aperture (because only that one molecule will see the light coming out of the tip). An image can be built by a raster scan of the tip over the surface to create an image.

The main down-side to NSOM is the limited number of photons you can force out a tiny tip, and the minuscule collection efficiency (if one is trying to collect fluorescence in the near-field). Other techniques such as ANSOM (see below) try to avoid this drawback.

Local enhancement / ANSOM / optical nano-antennas

Instead of forcing photons down a tiny tip, some techniques create a local bright spot in an otherwise diffraction-limited spot. ANSOM is apertureless NSOM: it uses a tip very close to a fluorophore to enhance the local electric field the fluorophore sees.[7] Basically, the ANSOM tip is like a lightning rod, which creates a hot spot of light.

Bowtie nanoantennas have been used to greatly and reproducibly enhance the electric field in the nanometer gap between the tips two gold triangles. Again, the point is to enhance a very small region of a diffraction-limited spot, thus improving the mismatch between light and nanoscale objects—and breaking the diffraction barrier.[8][9]

4Pi

A 4Pi Microscope is a laser scanning fluorescence microscope with an improved axial resolution. The typical value of 500-700 nm can be improved to 100-150 nm, which corresponds to an almost spherical focal spot with 5-7 times less volume than that of standard confocal microscopy.

The improvement in resolution is achieved by using two opposing objective lenses both of which focused to the same geometrical location. Also the difference in optical path length through each of the two objective lenses is carefully aligned to be minimal. By this, molecules residing in the common focal area of both objectives can be illuminated coherently from both sides and also the reflected or emitted light can be collected coherently, i.e. coherent superposition of emitted light on the detector is possible. The solid angle  that is used for illumination and detection is increased and approaches the ideal case. In this case the sample is illuminated and detected from all sides simultaneously.[10][11]

that is used for illumination and detection is increased and approaches the ideal case. In this case the sample is illuminated and detected from all sides simultaneously.[10][11]

Up to now, the best quality in a 4Pi microscope was reached in conjunction with the STED principle.[12]

Structured illumination microscopy (SIM)

There is also the wide-field structured-illumination (SI) approach to breaking the diffraction limit of light.[13][14] SI—or patterned illumination—relies on both specific microscopy protocols and extensive software analysis post-exposure. But, because SI is a wide-field technique, it is usually able to capture images at a higher rate than confocal-based schemes like STED (but SI is not actually superfast). The main concept of SI is to illuminate a sample with patterned light and increase the resolution by measuring the fringes in the Moiré pattern (from the interference of the illumination pattern and the sample). "Otherwise-unobservable sample information can be deduced from the fringes and computationally restored."[15]

SI enhances spatial resolution by collecting information from frequency space outside the observable region. This process is done in reciprocal space: The Fourier transform (FT) of an SI image contains superimposed additional information from different areas of reciprocal space; with several frames with the illumination shifted by some phase, it is possible to computationally separate and reconstruct the FT image, which has much more resolution information. The reverse FT returns the reconstructed image to a super-resolution image.

Spatially Modulated Illumination (SMI)

SMI microscopy is a light optical process of the so-called Point Spread Function-Engineering. These are processes that modify the Point Spread Function (PSF) of a microscope in a suitable manner to either increase the optical resolution, to maximize the precision of distance measurements of fluorescent objects that are small relative to the wavelength of the illuminating light, or to extract other structural parameters in the nanometer range. The Vertico SMI microscope achieves this in the following manner: The illumination intensity within the object range is not uniform, unlike conventional wide field fluorescence microscopes, but is spatially modulated in a precise manner by the use of one or two opposing interfering laser beams along the axis. The object is moved in high-precision steps through the wave field, or the wave field itself is moved relative to the object by phase shift. This results in an improved axial size and distance resolution.[16][17][18]

Deterministic functional techniques

RESOLFT microscopy is an optical microscopy with very high resolution that can image details in samples that cannot be imaged with conventional or confocal microscopy. Within RESOLFT the principle of STED microscopy [19][20] and GSD microscopy are generalized.

Stimulated emission depletion (STED)

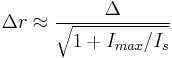

STED (Stimulated Emission Depletion microscopy) uses two laser pulses, the excitation pulse for excitation of the fluorophores to their fluorescent state and the STED pulse for the de-excitation of fluorophores by means of stimulated emission.[21][22][23][24][25] In practice, the excitation laser pulse is first applied whereby a STED pulse soon follows (But STED without pulses using continuous wave lasers is also used). Furthermore, the STED pulse is modified in such a way that it features a zero-intensity spot, which coincides with the excitation focal spot. Due to the non-linear dependence of the stimulated emission rate on the intensity of the STED beam, all the fluorophores around the focal excitation spot will be in their off state (the ground state of the fluorophores). By scanning this focal spot one retrieves the image. The FWHM of the PSF of the excitation focal spot can theoretically be compressed to an arbitrary width by raising the intensity of the STED pulse, according to equation (1).

()

()

∆r is the lateral resolution, ∆ is the FWHM of the diffraction limited PSF, Imax is the peak intensity of the STED laser, and Is is the threshold intensity needed in order to achieve saturated emission depletion.

The main disadvantage of STED, which has prevented its widespread use, is that the machinery is complicated. On the one hand, the image acquisition speed is relatively slow for large fields of view because of the need to scan the sample in order to retrieve an image. On the other hand, it can be very fast for smaller fields of view: Recordings with up to 80 frames per second have been shown. [26][27] Due to a large Is value associated with STED, there is a need for a high-intensity excitation pulse, which may cause damage to the sample.

Ground state depletion (GSD)

GSD microscopy or Ground State Depletion microscopy, uses the triplet state of a fluorophore as the off-state and the singlet state as the on-state, whereby an excitation laser is used to drive the fluorophores at the periphery of the singlet state molecule to the triplet state. This is much like STED, where the off-state is the ground state of fluorophores, which is why equation (1) also applies in this case. The Is value is smaller than in STED making super-resolution imaging possible at a much smaller laser intensity. Compared to STED though, the fluorophores used in GSD are generally less photostable and the saturation of the triplet state may be harder to realize.[28]

Spatially Structured Illumination Microscopy (SSIM)

SSIM (Spatially Structured Illumination microscopy) exploits the nonlinear dependence of the emission rate of fluorophores on the intensity of the excitation laser.[29] By applying a sinusoidal illumination pattern with a peak intensity close to that needed in order to saturate the fluorophores in their fluorescent state one retrieves moiré fringes. The fringes contain high order spatial information that may be extracted by computational techniques. Once the information is extracted a super-resolution image is retrieved.

SSIM requires shifting the illumination pattern multiple times, effectively limiting the temporal resolution of the technique. In addition there is a need of very photostable fluorophores due to the saturating conditions. These conditions also induce radiation damage to the sample that restricts the possible applications in which SSIM may be used.

SSIM section merged from Super-resolution microscopy page

Structured illumination microscopy only enhances the resolution only by a factor of 2 (because the SI pattern cannot be focused to anything smaller than half the wavelength of the excitation light). To further increase the resolution, one can introduce nonlinearities, which show up as higher-order harmonics in the FT. In reference,[15] Gustafsson uses saturation of the fluorescent sample as the nonlinear effect. A sinusoidal saturating excitation beam produces the distorted fluorescence intensity pattern in the emission. This nonpolynomial nonlinearity yields a series of higher-order harmonics in the FT.

Each higher-order harmonic in the FT allows another set of images that can be used to reconstruct a larger area in reciprocal space, and thus a higher resolution. In this case, Gustafsson achieves less than 50-nm resolving power, more than five times that of the microscope in its normal configuration.

The main problems with SI are that, in this incarnation, saturating excitation powers cause more photodamage and lower fluorophore photostability, and sample drift must be kept to below the resolving distance. The former limitation might be solved by using a different nonlinearity (such as stimulated emission depletion or reversible photoactivation, both of which are used in other sub-diffraction imaging schemes); the latter limits live-cell imaging and may require faster frame rates or the use of some fiduciary markers for drift subtraction. Nevertheless, SI is certainly a strong contender for further application in the field of super-resolution microscopy.

Examples for this microscopy are shown under 2.4 SIM (3D-SIM Microscopy)

Stochastic functional techniques

Localization Microscopy

Single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM) summarizes all microscopical techniques that achieve super-resolution by isolating emitters and fitting their images with the point spread function (PSF). Normally, the width of the point spread function (~ 250 nm) limits resolution. However, given an isolated emitter, one is able to determine its location with a precision only limited by its intensity according to equation (2). Here, Δloc is the localization precision, Δ is the FWHM of the PSF and N is the number of collected photons. This fitting process can only be performed reliably for isolated emitters (see Deconvolution), and interesting biological samples are so densely labeled with emitters that fitting is impossible when all emitters are active at the same time. SMLM techniques solve this dilemma by activating only a sparse subset of emitters at the same time, localizing these few emitters very precisely, deactivating them and activating another subset.

Generally, localization microscopy is performed with fluorophores. Suitable fluorophores reside in a non-fluorescent dark state for most of the time and are activated stochastically, most of the time with an excitation laser of low intensity. A readout laser stimulates fluorescence and bleaches or photoswitches the fluorophores back to a dark state, typically within 10-100 ms. The photons emitted during the fluorescent phase are collected with a camera and the resulting image of the fluorophore (which is distorted by the PSF) can be fitted with very high precision. Repeating the process several thousand times ensures that all fluorophores can go through the bright state and are recorded. A computer then reconstructs a super-resolved image.

The desirable traits of fluorophores used for these methods, in order to maximize the resolution, are that they should be bright. That is, they should have a high extinction coefficient and a high quantum yield. They should also possess a high contrast ratio (ratio between the number of photons emitted in the light state and the number of photons emitted in the dark state). Also, a densely labeled sample is desirable according to the Nyquist criteria.

The multitude of localization microscopy methods differ mostly in the type of fluorophores used.

SPDM: Localization Microscopy

SPDM (Spectral Precision Distance Microscopy), the first described localization microscopy technology 1997 is a light optical process of fluorescence microscopy, which allows position, distance and angle measurements on "optically isolated" particles (e.g. molecules) well below the theoretical limit of resolution for light microscopy.[30][31][32]

"Optically isolated" means that at a given point in time, only a single particle/molecule within a region of a size determined by conventional optical resolution (typically approx. 200-250 nm diameter) is being registered. This is possible when molecules within such a region all carry different spectral markers (e.g. different colors or other usable differences in the light emission of different particles). The structural resolution achievable using SPDM can be expressed in terms of the smallest measurable distance between two in their spatial position determined punctiform particle of different spectral characteristics ("topological resolution“). Modeling has shown that under suitable conditions regarding the precision of localization, particle density etc., the "topological resolution" corresponds to a "space frequency," which in terms of the classical definition is equivalent to a much-improved optical resolution.

SPDM is a localization microscopy that achieves an effective optical resolution several times better than the conventional optical resolution, represented by the half-width of the main maximum of the effective point image function. By applying suitable laser optical precision processes, position and distances can be measured with nanometer accuracy between targets with different spectral signatures.[33]

SPDMphymod

Localization microscopy for many standard fluorescent dyes like GFP, Alexa dyes and fluorescein molecules is possible if certain photo-physical conditions are present. With this so-called SPDMphymod (physically modifiable fluorophores) technology a single laser wavelength of suitable intensity is sufficient for nanoimaging [34] in contrast to other localization microscopy technologies that need two laser wavelengths when special photo-switchable/photo-activatable fluorescence molecules are used.

Based on singlet triplet state transitions it is crucial for SPDMphymod that this process is ongoing and leading to the effect that a single molecule comes first into a very long-living reversible dark state (with half-life of several seconds even) from which it returns to a fluorescent state emitting many photons for several milliseconds before it returns into a very long-living so-called irreversible dark state. SPDMphymod microscopy uses fluorescent molecules that are emitting the same spectral light frequency but with different spectral signatures based on the flashing characteristics. By combining two thousands images of the same cell, it is possible using laser optical precision measurements to record localization images with significantly improved optical resolution.[35]

Standard fluorescent dyes already successfully used with the SPDMphymod technology are GFP, RFP, YFP, Alexa 488, Alexa 568, Alexa 647, Cy2, Cy3, Atto 488 and fluorescein.

Photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM) and FPALM

PALM is single-molecule localization microscopy with fluorescent proteins. FPALM is the same method published concurrently under the same name.

Stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM)

STORM is a super-resolution imaging technique that utilizes sequential activation and localization of photoswitchable fluorophores to create high resolution images. During imaging, only an optically resolvable subset of fluorophores is activated to a fluorescent state at any given instant, such that the position of each fluorophore can be determined with high precision by finding the centroid positions of the single-molecule images of these fluorophores. The fluorophores are subsequently deactivated, and another subset is activated and imaged. Iterating this process allows numerous fluorophores to be localized and a super-resolution image to be constructed from these localizations. In principle any photoswitchable fluorophore can be used, and STORM has been demonstrated with a variety of different probes and labeling strategies. Using stochastic photoswitching of single fluorophores, such as Cy5,[36] STORM can be performed with a single red laser excitation source. The red laser both switches the Cy5 fluorophore to a dark state by formation of an adduct[37][38] and subsequently returns the molecule to the fluorescent state. Many other dyes can also be used for STORM.[39][40][41][42][43][44] In addition to single fluorophores, dye-pairs consisting of an activator fluorophore (such as Alexa 405, Cy2, and Cy3) and a photoswitchable reporter dye (such as Cy5, Alexa 647, Cy5.5, and Cy7) can be used for STORM.[45][46][47] In this scheme, the activator fluorophore, when excited near its absorption maximum, serves to reactivate the photoswitchable dye to the fluorescent state. Multicolor imaging has been performed by using different activation wavelengths to distinguish dye-pairs based on the activator fluorophore used[46][47][48] or using spectrally distinct photoswitchable fluorophores either with or without activator fluorophores.[39][49][50] In addition to organic dyes, photoswitchable fluorescent proteins can also be used.[50][51][52][53] Highly specific labeling of biological structures with photoswitchable probes has been achieved with antibody staining,[46][47][48][54] direct conjugation of proteins,[55] and genetic encoding.[50][51][52][53] STORM has also been extended to three-dimensional imaging using optical astigmatism, in which the elliptical shape of the point spread function encodes the x, y, and z positions for samples up to several micrometers thick,[47][54] and has been demonstrated in living cells.[50] To date, the spatial resolution achieved by this technique is ~20 nm in the lateral dimensions and ~50 nm in the axial dimension and the temporal resolution is as fast as ~0.5 - 1s.

Direct stochastical optical reconstruction microscopy (dSTORM)

dSTORM utilizes the photoswitching of a single fluorophore. In dSTORM, fluorophores are embedded in an oxidizing and reducing buffer system (ROXS) and fluorescence is excited. Sometimes, stochastically, the fluorophore will enter a triplet state, in which it is susceptible to the reducing components in the buffer. The fluorophore is reduced into a long-lived radical state, which is dark for several seconds.[56]

Software for localization microscopy

Localization microscopy depends heavily on software that can precisely fit the point spread function (PSF) to millions of images of active fluorophores within a few minutes. Since the classical analysis methods and software suites used in natural sciences are too slow to computationally solve these problems, often taking hours of computation for processing data measured in minutes, specialized software programs have been developed.

- rapidSTORM is currently (2011) the largest and most evolved software suite available.

Super-resolution Optical Fluctuation Imaging (SOFI)

It is possible to circumvent the need for PSF fitting inherent in single molecule localization microscopy (SMLM) by directly computing the temporal autocorrelation of pixels. This technique is called super-resolution optical fluctuation imaging (SOFI) and has been shown to be more precise than SMLM when the density of concurrently active fluorophores is very high.

Combination of techniques

3D Light microscopical nanosizing (LIMON) microscopy

3 D LIMON (Light MicrOscopical nanosizing microscopy) images using Vertico SMI are made possible by the combination of SMI and SPDM, whereby first the SMI and then the SPDM process is applied.

The SMI process determines the center of particles and their spread in the direction of the microscope axis. While the center of particles/molecules can be determined with a 1-2 nm precision, the spread around this point can be determined down to an axial diameter of approx. 30-40 nm.

Subsequently, the lateral position of the individual particle/molecule is determined using SPDM, achieving a precision of a few nanometers.[57]

As a biological application in the 3D dual color mode the spatial arrangements of Her2/neu and Her3 clusters was achieved. The positions in all three directions of the protein clusters could be determined with an accuracy of about 25 nm.[58]

References

- ^ Abbe, E. (1873). "Beitrage zur Theorie des Mikroskops und der mikroskopischen Wahrmehmung". Archiv für Mikroskopische Anatomie 9: 413–420. doi:10.1007/BF02956173. (German)

- ^ Neice, A. (2010). "Methods and Limitations of Subwavelength Imaging". Advances in Imaging and Electron Physics. Advances in Imaging and Electron Physics 163: 117. doi:10.1016/S1076-5670(10)63003-0. ISBN 9780123813145.

- ^ Cremer C, Cremer T (September 1978). "Considerations on a laser-scanning-microscope with high resolution and depth of field". Microsc Acta 81 (1): 31–44. PMID 713859.

- ^ WEM News and Views

- ^ "Fresnel Diffraction Applet" (Java applet). http://www.falstad.com/diffraction/. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ^ Cummings JR, Fellers TJ, Davidson MW (2007). "Specialized Microscopy Techniques - Near-Field Scanning Optical Microscopy". Olympus Microscopy Resource Center. http://www.olympusmicro.com/primer/techniques/nearfield/nearfieldintro.html. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ^ Sánchez EJ, Novotny L, Xie XS (1999). "Near-Field Fluorescence Microscopy Based on Two-Photon Excitation with Metal Tips". Phys Rev Lett 82 (20): 4014–7. Bibcode 1999PhRvL..82.4014S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.4014. http://link.aps.org/abstract/PRL/v82/p4014.

- ^ Schuck PJ, Fromm DP, Sundaramurthy A, Kino GS, Moerner WE (2005). "Improving the Mismatch between Light and Nanoscale Objects with Gold Bowtie Nanoantennas". Phys Rev Lett 94 (1): 017402. Bibcode 2005PhRvL..94a7402S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.017402. PMID 15698131. http://link.aps.org/abstract/PRL/v94/e017402.

- ^ Muhlschlegel P, Eisler H-J, Martin OJF, Hecht B, Pohl DW (2005). "Resonant optical antennas". Science 308 (5728): 1607–9. doi:10.1126/science.1111886. PMID 15947182. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/308/5728/1607.

- ^ Christoph Cremer and Thomas Cremer (1978): Considerations on a laser-scanning-microscope with high resolution and depth of fieldin M1CROSCOPICA ACTA VOL. 81 NUMBER 1 September, pp. 31—44 (1978)

Basic design of a confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscope & principle of a confocal laser scanning 4Pi fluorescence microscope, 1978 - ^ S.W. Hell, E.H.K. Stelzer, S. Lindek, C. Cremer (1994). "Confocal microscopy with an increased detection aperture: type-B 4Pi confocal microscopy". Optics Letters 19 (3): 222–224. Bibcode 1994OptL...19..222H. doi:10.1364/OL.19.000222. PMID 19829598. http://www.opticsinfobase.org/viewmedia.cfm?uri=ol-19-3-222&seq=0.

- ^ R. Schmidt, C.A. Wurm, S. Jakobs, J. Engelhardt, A. Egner, S.W. Hell (2008). "Spherical nanosized focal spot unravels the interior of cells". Nature Methods 5 (6): 539–544. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1214. PMID 18488034. http://www.nature.com/nmeth/journal/v5/n6/pdf/nmeth.1214.pdf.

- ^ Bailey B, Farkas DL, Taylor DL, Lanni F (November 1993). "Enhancement of axial resolution in fluorescence microscopy by standing-wave excitation". Nature 366 (6450): 44–8. doi:10.1038/366044a0. PMID 8232536.

- ^ Gustafsson MG (May 2000). "Surpassing the lateral resolution limit by a factor of two using structured illumination microscopy". J Microsc 198 (Pt 2): 82–7. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2818.2000.00710.x. PMID 10810003.

- ^ a b Gustafsson MG (September 2005). "Nonlinear structured-illumination microscopy: Wide-field fluorescence imaging with theoretically unlimited resolution". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (37): 13081–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0406877102. PMC 1201569. PMID 16141335. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1201569.

- ^ R. Heintzmann, C. Cremer (1999) Lateral modulated excitation microscopy: Improvement of resolution by using a diffraction grating. Proc. SPIE 3568: 185-196

- ^ US patent 7,342,717, filed 10th july 1997: Christoph Cremer, Michael Hausmann, Joachim Bradl, Bernhard Schneider Wave field microscope with detection point spread function

- ^ Reymann, J; Baddeley, D; Gunkel, M; Lemmer, P; Stadter, W; Jegou, T; Rippe, K; Cremer, C et al. (2008). "High-precision structural analysis of subnuclear complexes in fixed and live cells via spatially modulated illumination (SMI) microscopy". Chromosome research : an international journal on the molecular, supramolecular and evolutionary aspects of chromosome biology 16 (3): 367–82. doi:10.1007/s10577-008-1238-2. PMID 18461478.

- ^ Stefan W. Hell and Jan Wichmann (1994). "Breaking the diffraction resolution limit by stimulated emission: stimulated-emission-depletion fluorescence microscopy". Optics Letters 19 (11): 780–2. doi:10.1364/OL.19.000780. PMID 19844443. http://www.opticsinfobase.org/ol/viewmedia.cfm?URI=ol-19-11-780&seq=0.

- ^ Thomas A. Klar, Stefan W. Hell (1999). "Subdiffraction resolution in far-field fluorescence microscopy". Optics Letters 24 (14): 954–956. doi:10.1364/OL.24.000954. PMID 18073907. http://www.opticsinfobase.org/ol/viewmedia.cfm?uri=ol-24-14-954&seq=0.

- ^ Fernandes-Suares, M.; Ting, A. Y. (2008). "Fluorescent probes for super-resolution imaging in living cells". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 9 (12): 929–943. doi:10.1038/nrm2531. PMID 19002208.

- ^ Hell, S. W.; et al. (2007). "Far-Field Optical Nanoscopy". Science 316 (5828): 1153–1158. doi:10.1126/science.1137395. PMID 17525330.

- ^ Huang, Bo; Bates, M.; Zhuang, X. (2009). "Super resolution fluorescence microscopy". Annual Reviews of Biochemistry 78: 993–1016. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061906.092014. PMC 2835776. PMID 19489737. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2835776.

- ^ Willig, C.; et al. (2006). "STED microscopy reveals that synaptotagmin remains clustered after synaptic vesicle exocytosis". Nature Letters 440 (7086): 935–939. doi:10.1038/nature04592. PMID 16612384.

- ^ Patterson, G. H. (2009). "Fluorescence microscopy below the diffraction limit". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 20 (8): 886–893. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.08.006. PMC 2784032. PMID 19698798. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2784032.

- ^ Westphal, V.; et al. (2007). "Dynamic far-field nanoscopy". New Journal of Physics 9 (12): 435. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/9/12/435.

- ^ Westphal, V.; et al. (2008). "Video-Rate Far-FieldOptical Nanoscopy Dissects Synaptic Vesicle Movement". Science 320 (5873): 246–249. doi:10.1126/science.1154228. PMID 18292304.

- ^ Chmyrov, Andriy; et al. (2008). "Characterization of new fluorescent labels for ultra-high resolution microscopy". Photochemical & photobiological sciences 7 (11): 1378–1385. doi:10.1039/B810991P. PMID 18958325.

- ^ Gustafsson, M. G. L. (2005). "Nonlinear structured-illumination microscopy: Wide-field fluorescence imaging with theoretically unlimited resolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102 (37): 13081–13086. doi:10.1073/pnas.0406877102. PMC 1201569. PMID 16141335. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1201569.

- ^ J. Bradl, B. Rinke, A. Esa, P. Edelmann, H. Krieger, B. Schneider, M. Hausmann, C. Cremer (1996): Comparative study of three-dimensional localization accuracy in conventional, confocal laser scanning and axialtomographic fluorescence light microscopy. Proc. SPIE 2926: 201-206

- ^ US patent 6,424,421, filed 23rd December 1996: Christoph Cremer, Michael Hausmann, Joachim Bradl, Bernd Rinke Method and devices for measuring distances between object structures

- ^ R. Heintzmann, H. Münch, C. Cremer (1997) High-precision measurements in epifluorescent microscopy - simulation and experiment. Cell Vision 4: 252-253

- ^ Lemmer P, Gunkel M, Baddeley D, Kaufmann R, Urich A, Weiland Y, Reymann J, Müller P, Hausmann M, Cremer C (2007): SPDM – Light Microscopy with Single Molecule Resolution at the Nanoscale. In: Applied Physics B 2008; 93: 1–12

- ^ Reymann, J; Baddeley, D; Gunkel, M; Lemmer, P; Stadter, W; Jegou, T; Rippe, K; Cremer, C et al. (May 2008). "High-precision structural analysis of subnuclear complexes in fixed and live cells via spatially modulated illumination (SMI) microscopy". Chromosome research : an international journal on the molecular, supramolecular and evolutionary aspects of chromosome biology 16 (3): 367–82. doi:10.1007/s10577-008-1238-2. PMID 18461478.

- ^ Manuel Gunkel, Fabian Erdel, Karsten Rippe, Paul Lemmer, Rainer Kaufmann, Christoph Hörmann, Roman Amberger and Christoph Cremer (2009): Dual color localization microscopy of cellular nanostructures. In: Biotechnology Journal, 2009, 4, 927-938. ISSN 1860-6768

- ^ Zhuang, X. (2009). "Nano-imaging with Storm". Nature Photonics 3 (7): 365–367. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2009.101. PMC 2840648. PMID 20300445. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2840648.

- ^ Bates, M.; T. Blosser, X. Zhuang (2005). "Short-range spectroscopic ruler based on a single-molecule optical switch". Physical Review Letters 94 (108101).

- ^ Dempsey, G.; M. Bates, W. Kowtoniuk, D.Liu, R. Tsien, X. Zhuang (2009). "Photoswitching Mechanism of Cyanine Dyes". Journal of the American Chemical Society 131 (51): 18192–18193. doi:10.1021/ja904588g. PMC 2797371. PMID 19961226. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2797371.

- ^ a b Bock, H.; et al. (2007). "Two-color far-field fluorescence nanoscopy based on photoswitchable emitters". Applied Physics B 88 (2): 161–165. doi:10.1007/s00340-007-2729-0.

- ^ Folling, J.; et al." (2008). "Fluorescence nanoscopy by ground-state depletion and single-molecule return". Nature Methods 5 (11): 943–945. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1257. PMID 18794861.

- ^ Heilemann, M.; et al. (2008). "Subdiffraction-resolution fluorescence imaging with conventional fluorescent probes". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 47 (33): 6172–6176. doi:10.1002/anie.200802376.

- ^ Heilemann, M.; S. van de Linde, A. Mukherjee, M. Sauer (2009). "Super-resolution imaging with small organic fluorophores". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 48 (37): 6903–6908. doi:10.1002/anie.200902073.

- ^ Vogelsang, J.; T. Cordes, C. Forthmann, C. Steinhauer, P. Tinnefeld (2009). "Controlling the fluorescence of ordinary oxazine dyes for single-molecule switching and superresolution microscopy". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 (20): 8107–8112. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811875106.

- ^ Lee, H.; "et al." (2010). "Superresolution Imaging of Targeted Proteins in Fixed and Living Cells Using Photoactivatable Organic Fluorophores". Journal of the American Chemical Society 132 (43): 15099–15101. doi:10.1021/ja1044192. PMC 2972741. PMID 20936809. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2972741.

- ^ Rust, M.; M. Bates, X. Zhuang (2006). "Sub-diffraction-limit imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM)". Nature Methods 3 (10): 793–796. doi:10.1038/nmeth929.

- ^ a b c Bates, M.; B. Huang, G. Dempsey, X. Zhuang (2007). "Multicolor Super-resolution Imaging with Photo-switchable Fluorescent Probes". Science 317 (5845): 1749–1753. doi:10.1126/science.1146598. PMC 2633025. PMID 17702910. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2633025.

- ^ a b c d Huang, B.; S. Jones, B. Brandenburg, X. Zhuang (2008). "Whole cell 3D STORM reveals interactions between cellular structures with nanometer-scale resolution". Nature Methods 5 (12): 1047–1052. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1274. PMC 2596623. PMID 19029906. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2596623.

- ^ a b Dani, A.; B. Huang, J. Bergan, C. Dulac, X. Zhuang (2010). "Super-resolution Imaging of Chemical Synapses in the Brain". Neuron 68 (5): 843–856. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.021. PMC 3057101. PMID 21144999. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3057101.

- ^ Testa, I.; "et al." (2010). "Multicolor Fluorescence Nanoscopy in Fixed and Living Cells by Exciting Conventional Fluorophores with a Single Wavelength". Biophysical Journal 99 (8): 2686–2694. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.012. PMC 2956215. PMID 20959110. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2956215.

- ^ a b c d Jones, S.; S. Shim, X. Zhuang (2011). "Fast three-dimensional super-resolution imaging of live cells". Nature Methods 8 (6): 499–508. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1605. PMC 3137767. PMID 21552254. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3137767.

- ^ a b Betzig, E.; et al. (2006). "Imaging Intracellular Fluorescent Proteins at Nanometer Resolution". Science 313 (5793): 1642–1645. doi:10.1126/science.1127344. PMID 16902090.

- ^ a b Hess, S.; T. Giririjan, M. Mason (2006). "Ultra-High Resolution Imaging by Fluorescence Photoactivation Localization Microscopy". Biophysical Journal 91 (11): 4258–4272. doi:10.1529/biophysj.106.091116. PMC 1635685. PMID 16980368. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1635685.

- ^ a b Wang, W.; G. Li, C. Chen, S. Xie, X. Zhuang (2011). "Chromosome organization by a nucleoid-associated protein in live bacteria". Science 333 (6048): 1445–1449. doi:10.1126/science.1204697. PMID 21903814.

- ^ a b Huang, B.; W. Wang, M. Bates, X. Zhuang (2008). "Three-dimensional Super-resolution Imaging by Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscopy". Science 319 (5864): 810–813. doi:10.1126/science.1153529. PMC 2633023. PMID 18174397. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2633023.

- ^ Wu, M.; B. Huang, M. Graham, A. Raimondi, J. Heuser, X. Zhuang, P. Camilli (2010). "Coupling between clathrin-dependent endocytic budding and F-BAR-dependent tubulation in a cell-free system". Nature Cell Biology 12 (9): 902–908. doi:10.1038/ncb2094. PMID 20729836.

- ^ Heilemann et al, 2008, Angewandte Chemie and van de Linde et al, 2011, Photochem. Photobiol. Sci

- ^ Baddeley D, Batram C, Weiland Y, Cremer C, Birk UJ.: Nanostructure analysis using Spatially Modulated Illumination microscopy. In: Nature Protocols 2007; 2: 2640–2646

- ^ Rainer Kaufmann, Patrick Müller, Georg Hildenbrand, Michael Hausmann & Christoph Cremer (2010): Analysis of Her2/neu membrane protein clusters in different types of breast cancer cells using localization microscopy, Journal of Microscopy 2010, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2010.03436.x